Requiem for a loose cannon: Jim Ryan, 1937-2016

I found this 8” x 10” photo of my dad with a couple of Derrick Dolls—the Houston Oilers cheerleaders—in a frame among his stuff.

It took me a long time to find the perfect description of my dad. After we lost my mom, people would ask about my remaining parent—where he lived, if we were close, what he was like. I’m not sure when I settled on it, but I started saying, “He’s a loose cannon.”

Maybe it baffled people, but I like to think it conveyed just enough about his personality to show that life was seldom boring with Jim Ryan. It follows that the world is a less interesting place without him now. He died around 11 p.m. on August 3.

“Loose cannon” isn’t a euphemism for a personality disorder—my dad wasn’t bipolar or anything. He wasn’t an addict or con man. He was simply a funny hothead who did what he wanted. He was often charming and occasionally terrifying. He could be the funniest guy in the room or the biggest asshole I knew. I spent my formative years seeking his approval and anticipating the day I’d move away from him. That was life with a loose cannon.

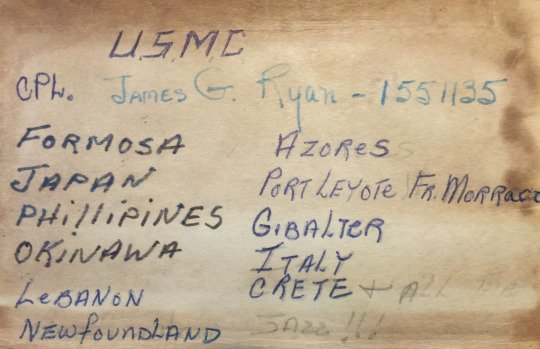

My dad grew up in East Hartford, Connecticut, a blue-collar factory town that he was eager to escape as soon as high school ended in 1956. He achieved that by joining the Marine Corps, which took him all over the world—and to some of its “finest cathouses,” as he told me later.

The places he visited while in the Marine Corps.

His time in the service would be the defining experience of his life, so much so that he joined the Texas Army National Guard in the early ’80s and returned to full-time active duty not long after that. He had other jobs when I was very young, but I knew him as a soldier. That conjures a lot of stereotypes, none of which fit my dad. He wasn’t some flag-waving zealot, or a barking drill-instructor type, or the cold, distant military man ill at ease with civilians. Growing up, we’d put a flag out for the patriotic holidays, but I did that, not my dad. He didn’t make a big deal out of his service.

But he went back to it as his life drew to a close. A couple of weeks before he died, he mentioned that his military experience gave him some measure of peace with death, because the possibility of it hung over life in the Corps. Born in 1937, my dad was the perfect age to miss all the major wars of his lifetime—too young for WWII and Korea, discharged before Vietnam, though, oddly, he came close to Desert Storm in his 50s—but he experienced a few close calls while in the Marines. During the last week of his life, in the doped-up delirium that kept him in a semi-dream state, he would ask me and my sisters about the location of barracks, getting the proper sign-off on orders, and pulling rank:

Dad: “I think I’ll give myself an extra stripe.”

Me: “An extra stripe?”

Dad: “He gave himself an extra stripe.”

Me: “Can he do that?”

Dad: “He did.”

We yes-anded the shit out of my father during his final days, like Tuesdays With Morrie by way of Del Close. My improvisational skills occasionally faltered, like when he woke up and said to me, “Gutterball—1.386 on the odometer” and “Alberto? That’s my name in Spanish.” My dad was dropping some next-level scene work on us.

Ever the journalist, I took notes and recorded a few of our conversations before the drugs took away his lucidity. Really, I’ve been taking notes on my dad my whole life, because he offered a fount of material.

It was to be expected that he’d loudly exclaim “I thought we won the war!” when he’d get the check at Benihana. (“Jimmy!” my mom would say, shocked.) He was the kind of guy who’d go on a water ride at an amusement park then strip down to his tighty-whities in the men’s room afterward to dry his clothes off with the hand dryer. (That image, and the deeply confused expressions on the faces of the guys in the AstroWorld bathroom, are forever seared into my brain.) Another time he took me to a water park and wore these pale-yellow trunks that turned translucent when wet, putting his penis on prime display for his fellow Fame City Waterworks patrons.

His nudity was a fact of life at the Ryan household. He’d walk around naked after showers. He’d soak naked in the hot tub in our backyard after playing softball, then stand up, toweling off his balls and ass to the easy view of our neighbors and whoever happened to be in our family room, with its three big plate-glass windows facing the hot tub. My friends got used to it, and I grew accustomed to being mortified.

And walking on eggshells. When I say dad was a loose cannon, maybe I should emphasize the “cannon” part. He mellowed in his 60s, but I have vivid memories of his explosions and the palpable fear we had of them growing up. My sisters, 11 and 13 years older than I am, experienced less of it, but we all knew dad’s scary side. I was a hyper-sensitive mama’s boy, and her acute anxiety about my unpredictable father was imprinted on me at an early age.

Some of my memories lack context. I remember a big explosion when I was very young that left my mom crying and—this part I remember most—saying she would run away where no one could find her, but I don’t remember what caused it. I think it had something to do with my dad wanting to bring groceries in from the car a certain way. That’s life with a loose cannon: Small things could trigger big outbursts.

When I was in elementary school, I remember his storming out of a restaurant and walking home, but not why. It may have been because I didn’t like my food. I remember he and my mom picking me up from the airport when I was like 9 or 10 and my dad nearly getting into a fistfight with a cab driver because of where he parked. I remember his taking me to Burger King when I was like 13 and almost coming to blows with the guy behind us in the drive-thru who had his music too loud. The only thing that stopped it from escalating was my pleading with him. Just a couple years ago, my dad told one of my sisters that story and found it funny. “Do you remember that?” he asked. “Oh yes,” I said, my terse reply conveying that my young self found it terrifying, and my grown-up self saw little humor in it.

He knew better than to joke about (or even mention) our infamous vacation to New Mexico with my mom’s brother and his family. My dad’s constant prickliness erupted into an argument with my sister one day, and, the stress overtaking my 16-year-old self, I shouted, “Why don’t both of you shut the fuck up?” They’d never heard me cuss before, much less advise my dad to f-something. He snapped and came bounding to smack me around. My mom tried to intervene, but he only relented when I said, “I’m your son!”—a line I swiped from The Simpsons, when Bart said it to get Homer to stop strangling him. (As always, The Simpsons did it first.)

Not to get all “Father Of Mine,” but I’ve thought a lot about my childhood now that I have a little girl. Let’s be clear: I didn’t have it bad, especially compared to people who endured physical, emotional, or sexual abuse from a parent. My experiences left me with an anxious predilection for defusing confrontation, not deep emotional scars. Still, I never want to see the fear on my daughter’s face that my mom undoubtedly saw on mine.

We lost my mom 14 years before my dad. In 2000, she was diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer, one of the most aggressive types and one with a dispiritingly low survival rate. Because life can be especially cruel, my parents’ house in Houston flooded the following summer, right when doctors discovered the cancer had spread to mom’s liver. We all gathered in Houston to help with the house and accompany her to a follow-up appointment, where we expected to be told she had little time left.

Dread hung heavily over everything that weekend, and the panicked look on my mom’s face tore my heart out. The loose cannon decided this was the perfect context to tell me a story about banging a prostitute while stationed in Lebanon. As we dropped off boxes at the storage space, he set the scene: Marines in Lebanon took frequent fire from Muslim guerillas, and when my dad entered this woman’s room, he noticed she had a window opening onto a fire escape or stairwell—meaning someone could lie in wait for my dad to get down to business, then climb up to take out an American soldier. He decided the best defense was a good offense: “I had the prostitute in one hand and my gun in the other!”

At the time, the disconnect between his story and the reality of my mom’s situation was a lot to process, but 15 years later, I appreciate it. That’s my only happy memory of what was otherwise the worst weekend of my life.

My mom would die roughly 10 months later, upending our family order and leaving all of us unsteady. My dad relied on my mom for most things: She was the breadwinner, she handled the bills, and she did the bulk of the parenting. It’s not that my dad was completely inattentive; he just did his own thing, and it was hard to keep up with my mom’s boundless love for her children. Yet he was all we had left.

Grief strengthened the bond between us—dad was our strongest link to mom, and we were his. We crowded on his bed the week after my mom died to watch Crossing Over, a show hosted by a guy who claimed to communicate with the dead loved ones of people in his studio audience. We needed some kind of reassurance that she was still out there, somewhere.

I have another great memory of lying on that bed and talking to my dad about his early life. Needing to express his loose cannonosity, he’d gotten a few tattoos in the service—a USMC bulldog, a gravestone, a diamond, maybe another one I’m forgetting. He later decided to get rid of all but the bulldog, but this being the pre-laser days, tattoo removal entailed freezing the skin and literally sanding it. Shockingly, it wasn’t a very effective system, but it sounds badass.

We eventually settled into a comfortable rhythm. I called him on Sundays and saw him on holidays. He’d occasionally visit Chicago, but he didn’t like the city much, and the loose cannon’s racial attitudes could make him a liability in public. Keeping him indoors could be challenging too, because the hearing loss he had since childhood meant he cranked up Fox News to roughly 110 decibels at all times.

In 2014, when I moved to New York, he offered to ride in the moving truck with me. I drove the whole way, but he was good company, even though we had to stop a lot so he could walk around or go to the bathroom. I attributed it to his being 77, but none of us knew then he had a tumor growing in his pelvis.

We wouldn’t learn that for more than two years. In 2015, dad moved from Houston to a featureless Denver suburb called Broomfield to live with my sister Nancy and her family. My other sister, Melissa, would relocate there with her family too, and for the first time in decades, most of my family lived in one place.

My sisters noticed it first. Although my dad played softball until he was 74, he was also a couch potato, so his being more sedentary than usual didn’t set off any alarms. But he began sleeping all the time, lost a lot of weight, and didn’t have much of an appetite. I hardly spoke to him, because he was never around when I called. Pretty soon Nancy and Melissa were telling me, with greater and greater urgency, to come visit.

While I looked for a cheap flight, they took him to the doctor. Tests revealed nothing, though that didn’t assuage Nancy and Melissa’s concerns. Nancy took him to the ER one morning and insisted on a chest x-ray. It revealed lungs riddled with tumors, and a CAT scan found a football-sized tumor on his pelvis, with lesions on his liver, spleen, and lungs. The official diagnosis was sarcoma—soft-tissue cancer—that had metastasized. There would be no viable treatment.

Not that the loose cannon would’ve wanted it. He’d watched my 60-year-old mother struggle through surgery and rounds of chemo and radiation to no avail. He was coming up on his 79th birthday with cancer far more advanced than the insidiously aggressive cancer my mom had endured. “I’ve had a good life,” he told us. And that was that.

Dad had hospice care at my sister’s home, with weekly visits from a nurse and an ample supply of potent opiates to temper his pain. My sisters and I speculated that my dad would check out once it became too much—his own mother got so worked up about going into a nursing home, she died two days after they admitted her. My dad wouldn’t go for the death-bed dramatics. “I bet we’ll go in one morning, and he’ll be gone,” Melissa said. That sounded right to me.

The last week of his life, I flew in on a Tuesday morning to find him his usual self, chatty and good-humored, all things considered. The pain—sorry, “discomfort,” he never called it “pain”—started ramping up a couple of days later. I was supposed to fly to Miami for work on Thursday, and that morning, he asked me a few times, “So you’re leaving soon?” I couldn’t tell if he was making conversation or hinting at something else. When I stepped out of the room, Nancy asked if he wanted me to stay, and he said yes. I pushed my return flight to Sunday, but I got the feeling he didn’t want me to leave. “Dad, I don’t have to go back,” I told him. He thought for a moment. “Kyle, I’m having a hard time here,” he said, adding he could use my help. I told him I was happy to stay. “I hate to keep you from your family,” he said. “But you’re my family,” I replied quickly. He smiled. That would be one of our last lucid exchanges.

He took a turn on Sunday, and I thought for sure we’d lose him that night. My sisters and I kept a vigil by his bed into the wee hours, playing music he liked and assuring him it was okay to go. But his breathing improved and, as it grew later, we grew tired. We decamped to nearby sofas, and on our way out of the room, dad called out, “Later!” He wasn’t interested in an audience, especially when he was trying to rest.

He stabilized enough that the hospice nurse said he wasn’t “actively dying.” It could be a few days, or it could be a week. I’d been away from my little girl for what felt like an eternity and missed her desperately, so I decided (with the urging of my sisters) to sneak home for a couple of days. I flew into Chicago late Tuesday night. Dad died Wednesday night.

He never woke up after I left, and his departure was abrupt: Melissa had given him some medicine, then noticed his color changed a few minutes later. Foam came from his mouth. She ran to get Nancy, and in the seconds that transpired, he was gone.

No death-bed speeches, no audience, no dramatics. The loose cannon goes his own way.